Horror often moves fast - to stay alive, you have to be one step ahead of the killer - so one cannot linger with the dead. Consider this scene from The Walking Dead, Season 1, Episode 5 in which Andrea's younger sister - an innocent - falls prey when the camp is over run by a zombie horde. Andrea kneels over her sister, mourning her death. "Amy, I am sorry," she says "for not ever being there. I always thought there would be more time." But there simply isn't time. The mourning turns into horror as Amy gradually revives. First a soft breathing, then the reanimated corpse slowly almost tenderly raises her arms as if to embrace Andrea, then snarling and attacking as a fleshing-eating zombie. Andrea pulls out a pistol, whispers "I love you" as she shoots her zombie sister in the head.

(Caveat: In the full scene, Andrea is actually granted much more time to mourn - an uncomfortable and excessive amount of time for some of the group. She sits with her sister's corpse for hours, maybe a whole day or more, holding a sort of vigil. In fact, the group is busy burying other dead people, not wanting these deaths to be unrecognized and devoid of sentiment. The group grants her and themselves some time and space to mourn. But only contingently - they hover around her in their nervous distress, interrupting politely but insistently to hurry her up, to end the delay, so the group can move on. Everyone knows that the sister's corpse will turn into a zombie sooner or later.)

Here we see both the theme of impurity -- the sister's corpse is infected, impure, it must be destroyed. To live means to separate from it, to avoid being infected by it. The dead are contamination, waste material. There is also the theme of haste - there is no time to mourn because this must be dealt with immediately, lingering makes us all more vulnerable. Perhaps mourning is ultimately stupid or misguided from an existential perspective because the person is no longer there and what returns is a threat.

At time in horror, the dead are protrayed as responsible for or at fault for their demise. If they had been smarter, faster, stronger, more observant, more ethical then perhaps they would have avoided death. The silly frivolous sexually promiscuous teenagers of the Halloween and Friday the 13th films may be examples of this. The victims in these slasher films tend to be those engaged in "illicit sex, illegal drugs, and general adolescent irresponsibility" while the "final girl" fights back, fortified "because she represses these very impulses and desires, in particular, retaining her virginity. . . .Abstinence and rectitude evidently give final girls the power to fight back and survive" (Rick Worland, The Horror Film: An Introduction, 228-29). Their death is a judgment, the killer's vengeance is something like a secular wrath of God that is visited upon the sexually immoral. Jess Peacock writes "In the world of Friday the 13th where teens take drugs, engage in wanton sex, and…gasp…go skinny dipping, Jason Voorhees appears as a nightmarish fundamentalist Christian champion, God’s unstoppable angel of Death. He imposes judgment on those who fail to sprinkle their door with the blood of moral uprightness. He is the arrow straining against Jonathan Edwards’ righteous bow [referencing his sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God"]. In these examples, the dead aren't mourned, cannot be mourned, because they just got what they deserved.

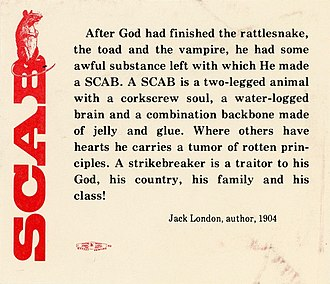

This theme came up in a question I was asked at the AAR in San Antonio. In Old Gods of Appalachia Season 1, Episode 2, a group of African-American workers are brought into Barlo, Kentucky to break the strike at the Old Number Seven mine. These workers are all killed in the mine explosion. In my reading, the podcast portrays these strike-breakers in a sympathetic light. They are victims of the merciless capitalist system, exploited workers reduced to a state of inhumane vulnerability without protection, dignity, or even names. The podcast portrays their deaths and their subsequent internment in anonymous mass graves as a moral offense.Why aren't they mourned? Why doesn't Old Gods take a moment to stand at the mass grave of these exploited workers and lament? It was a missed opportunity in Old Gods - these scabs come back as zombies to wreck the town, to take vengeance, and to enact a sort of moral accounting for their deaths. But there is no sense of memorializing them. Perhaps Old Gods could have taken time to treat these workers with more complexity and compassion, to tell those stories or to erect a virtual monument to the memory of those who died in the mines. However, there isn't really any lingering with these dead. There is a buildup of moral outrage, but not a transformation in the audience's perspective.

Image #1: AI image generated by Bing Copilot Designer with the prompt "mourner standing by a lonely overgrown grave in the woods dark colors drawing sketch pastels"

Image #2: AI image generated by Bing Copilot Designer with the prompt "worn overgrown gravestone cemetery gloomy trees mourner standing laying flowers crying sketch drawing black and white"